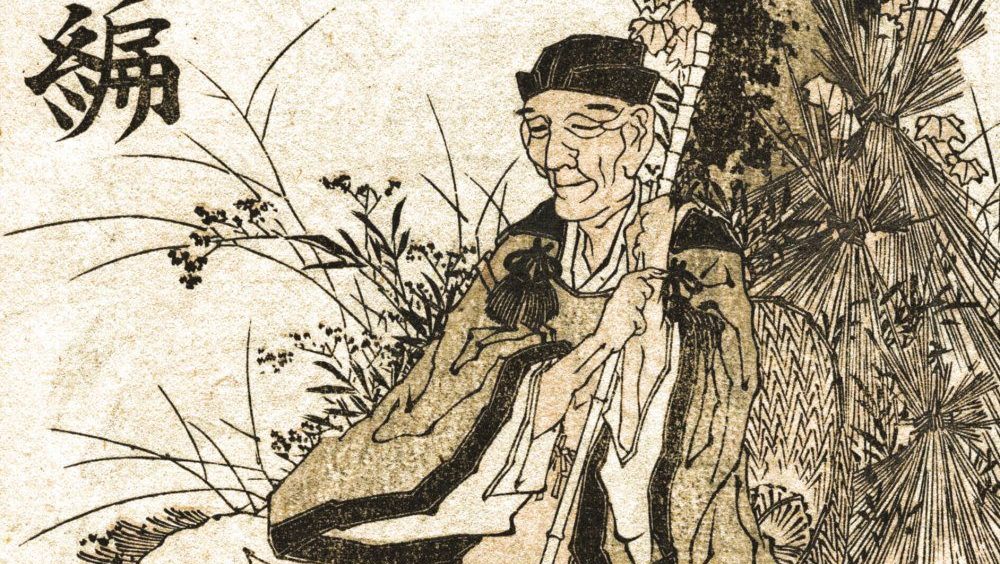

Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694) is the most celebrated poet of Japan’s Edo period and a master of the haiku, the short poetic form that distills profound insight into the natural and spiritual worlds. Blending Zen Buddhist awareness with classical Japanese aesthetics, Bashō elevated haiku from playful verse to a deeply contemplative art. His works capture fleeting moments — the cry of a bird, a falling leaf, the quiet of a journey — revealing eternity within the ordinary.

Early Life and Education

Bashō was born Matsuo Kinsaku in 1644 near Ueno in Iga Province (now Mie Prefecture), Japan. His father was a low-ranking samurai, and though his family was not wealthy, Bashō received a solid education in classical Chinese and Japanese literature.

In his youth, Bashō served as a page to a local lord whose passion for poetry sparked his own interest in verse. When his patron died, Bashō abandoned samurai life and devoted himself to poetry and study. He moved to Kyoto and later to Edo (modern Tokyo), where he began participating in the popular haikai no renga — linked-verse poetry — which combined wit with observation of everyday life.

Literary Career and Major Works

By the 1670s, Bashō had become a respected poet and teacher in Edo. Seeking a simpler, more authentic existence, he withdrew from urban life, building a small hut by a banana tree (bashō) — from which he took his poetic name. His poetry evolved from clever wordplay to spiritual reflection, shaped by his growing devotion to Zen Buddhism and nature.

Bashō’s early collections, such as Kai ōi (Shell Matching, 1672) and The Sea Shell Game (1672), established his reputation, but his mature works transformed Japanese poetry. In Nozarashi Kikō (The Records of a Weather-Exposed Skeleton, 1684), he chronicled his first long journey on foot, using travel as both physical and spiritual pilgrimage.

His masterpiece, Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the Deep North, 1689), written during a 2,400-kilometer journey through northern Japan, combines prose and haiku into a meditative travel diary. It remains one of Japan’s literary treasures, celebrated for its serene tone and keen sensitivity to nature and impermanence.

Style, Themes, and Influence

Bashō’s haiku reflect the principles of Zen and wabi-sabi — simplicity, impermanence, and beauty found in transience. His poems are marked by clarity and understatement, inviting the reader to perceive depth in the smallest details. He believed poetry should arise from direct experience, writing, “Learn of the pine from the pine.”

Common themes in his work include solitude, the passage of time, the changing seasons, and the unity of humanity and nature. His haiku often juxtapose contrasting images — motion and stillness, joy and sorrow — to evoke emotional resonance.

One of his most famous haiku captures this essence:

An old silent pond—

A frog jumps into the pond,

Splash! Silence again.

Bashō’s influence on Japanese literature is immeasurable. He transformed haiku from a social pastime into a serious art form and inspired generations of poets, including Yosa Buson, Kobayashi Issa, and Masaoka Shiki. His meditative vision also attracted Western admirers such as Ezra Pound, Jack Kerouac, and Gary Snyder, who saw in his work a bridge between poetry and mindfulness.

Later Life and Legacy

Bashō continued to travel throughout Japan in his later years, viewing poetry as both discipline and spiritual practice. Despite periods of ill health, he remained devoted to his art, teaching disciples and refining his philosophy of simplicity and truth.

He died in Osaka on November 28, 1694, during one of his journeys, surrounded by his followers. His last recorded haiku reflects his calm acceptance of life’s impermanence:

Falling sick on a journey,

My dreams go wandering still

Over the withered fields.

Bashō’s influence endures in Japan and beyond. His haiku have been translated into dozens of languages, and his quiet wisdom continues to shape global perceptions of nature, art, and consciousness.

Notable Works

- The Records of a Weather-Exposed Skeleton (Nozarashi Kikō, 1684)

- The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Oku no Hosomichi, 1689)

- The Knapsack Notebook (Oi no Kobumi, 1687)

- A Visit to Kashima Shrine (Kashima Kikō, 1687)

Related Poets

Saigyō, Yosa Buson, Kobayashi Issa, Masaoka Shiki, Ryōkan