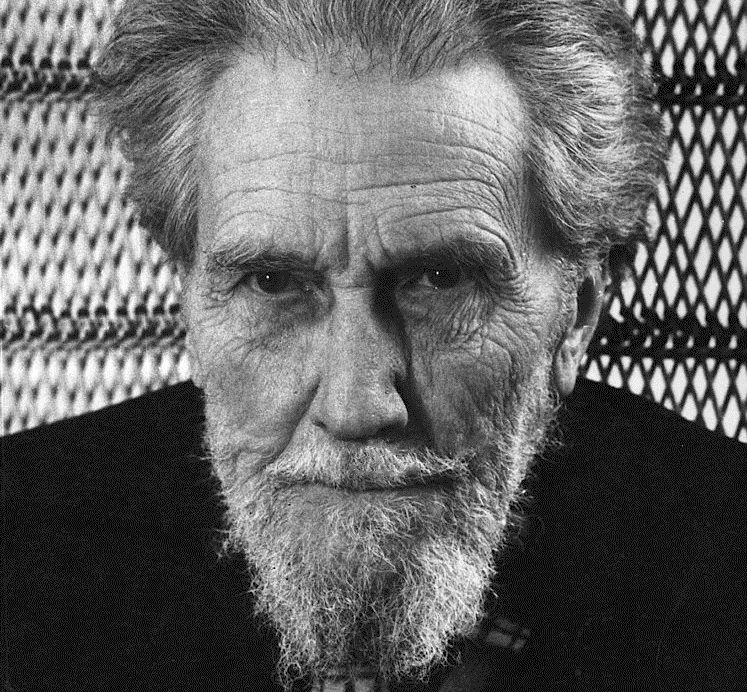

Ezra Pound (1885–1972) was one of the most influential and controversial figures in twentieth-century literature. A poet, critic, and visionary, Pound played a pivotal role in shaping modernist poetry through his advocacy of precision, economy, and innovation in language.

His editorial guidance and mentorship of writers such as T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, and H. D. (Hilda Doolittle) helped define an entire era of literary experimentation. Though his later years were marred by political controversy, Pound’s influence on the shape and direction of modern literature remains immeasurable — his insistence on clarity, precision, and musical rhythm in verse changed the course of twentieth-century poetry.

Early Life and Education

Pound was born in Hailey, Idaho, but grew up in Pennsylvania in an educated, middle-class family. His academic gifts emerged early, and he enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania before transferring to Hamilton College, where he earned a degree in philosophy and literature. Returning to Penn for graduate work, he met poets H. D. and William Carlos Williams, forming lifelong creative relationships that would shape modernist poetry.

After a brief teaching stint at Wabash College, which ended controversially due to his unconventional behavior, Pound left for Europe in 1908. London became his intellectual home and the center of his early career. Immersed in the literary ferment of the city, he began publishing prolifically and advocating a new aesthetic vision for poetry: one that rejected ornament and embraced clarity, rhythm, and the image as the heart of meaning.

Literary Career and Major Works

Pound’s first major collection, A Lume Spento (1908), was published in Venice and signaled the arrival of a distinctive new voice. In London, he released Personae (1909) and Exultations (1909), refining his early style through translations, adaptations, and original lyrics steeped in classical and medieval influences. He quickly established himself as a literary catalyst, editing anthologies, writing criticism, and promoting other poets.

By 1912, Pound became the leading advocate of Imagism, a movement that emphasized precision, clarity, and the economy of language. His editorial work with H. D. and Richard Aldington helped to crystallize Imagist principles that revolutionized modern verse. Later, his collaboration with T. S. Eliot on The Waste Land (1922) demonstrated his extraordinary editorial skill — Eliot himself credited Pound as “il miglior fabbro,” or “the better craftsman.”

In the 1920s, Pound launched the Cantos, his life’s work and one of the most ambitious poetic projects of the modern era. Combining history, myth, economics, and personal reflection, The Cantos sought to create a new epic for the modern age. Though incomplete at his death, the work spans decades and reflects both the brilliance and contradictions of his vision.

Style, Themes, and Influence

Pound’s poetry is marked by compression, allusion, and a fascination with language as a living, transformative force. He drew from classical, Chinese, and Provençal sources, weaving together cultures and epochs to illuminate patterns of human civilization. His command of form and rhythm, and his insistence on the precision of the image, gave modern poetry a new discipline and vitality.

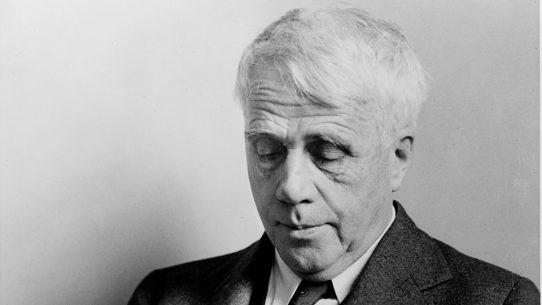

His influence extended beyond his own writing. Pound championed the works of T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, and Robert Frost, among others. His editorial interventions — particularly in Eliot’s The Waste Land and Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man — shaped some of the century’s defining texts. His ideas about the relationship between art, language, and economics also influenced generations of poets and theorists.

Yet Pound’s political views during the 1930s and 1940s, including his support for Italian fascism and his wartime broadcasts, cast a lasting shadow on his reputation. His imprisonment and subsequent confinement in St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., raised complex questions about genius, morality, and the responsibilities of the artist.

Later Life and Legacy

After his release from St. Elizabeths in 1958, Pound returned to Italy, where he lived in relative seclusion. In his final years, he spoke little and wrote sparingly, expressing remorse for some of his past actions and doubts about his life’s work. Despite these controversies, his contributions to literature remained immense. His later writings, including the Pisan Cantos (1948), reveal moments of introspection and lyrical beauty amid despair.

Pound died in Venice in 1972, leaving behind a body of work that continues to provoke admiration and debate. His innovations in form, rhythm, and language reshaped poetry, while his complex life serves as both inspiration and cautionary tale.

Notable Works

Among Pound’s early works, A Lume Spento (1908) and Personae (1909) showcase his fascination with history and his evolving mastery of form. His role in shaping Imagism culminated in the anthology Des Imagistes (1914), which became a manifesto for modern poetry.

Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920) stands as a turning point in his career, blending satire and self-reflection to critique the emptiness of postwar culture. His magnum opus, The Cantos (1917–1969), represents one of the most ambitious poetic undertakings of the twentieth century — an unfinished epic exploring history, culture, and human aspiration.

Pound’s critical essays, collected in works such as Literary Essays of Ezra Pound (1954) and ABC of Reading (1934), remain foundational texts for understanding modernist aesthetics. Together, these writings and poems define his legacy as both the architect and provocateur of modern poetry.