Introduction

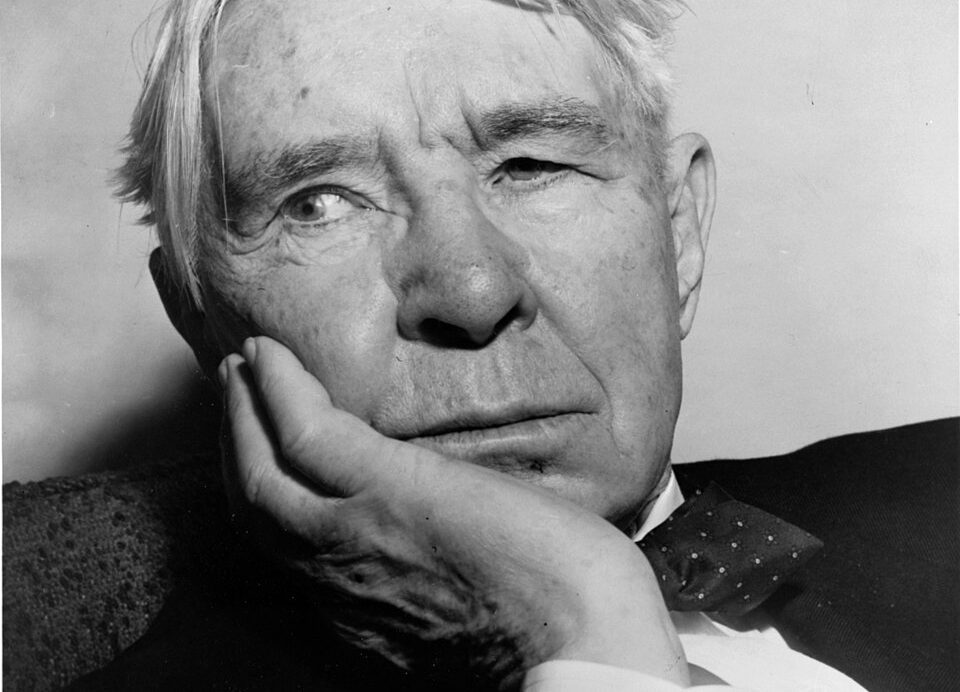

Carl Sandburg (1878–1967) was one of America’s most beloved poets, renowned for his portrayals of ordinary people and his vivid depictions of the nation’s landscape, labor, and spirit. A Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, biographer, and journalist, Sandburg’s work blended realism, idealism, and a deep democratic faith in humanity.

His voice, both lyrical and rough-hewn, captured the rhythm of modern America in transition—from the farms and factories of the nineteenth century to the cities and conflicts of the twentieth.

Early Life and Education

Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois, the son of Swedish immigrants who instilled in him a strong work ethic and respect for common labor. His father worked on the railroads, and young Carl left school at thirteen to help support the family through a series of odd jobs—milkman, bricklayer, and porter among them. These experiences gave him firsthand insight into the struggles of working-class Americans, a theme that would define his poetry.

He briefly attended Lombard College, where he came under the mentorship of Philip Green Wright, a professor who recognized his talent and published his early poems. Although Sandburg did not complete his degree, his time at Lombard expanded his intellectual and political horizons. He became deeply interested in social justice, democracy, and the labor movement—ideals that would later shape both his writing and public life.

Literary Career and Major Works

After serving in the Spanish–American War, Sandburg worked as a journalist in Chicago, a city that became the heart of his creative identity. His first major collection, Chicago Poems (1916), established him as a powerful new voice in American poetry. Its raw, free-verse style and celebration of the city’s energy and grit marked a break from traditional poetic conventions. The famous opening line — “Hog Butcher for the World, / Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat” — announced a poet who would speak for the people, not above them.

He followed this success with Cornhuskers (1918), which won the Pulitzer Prize and furthered his reputation as a poet of the American heartland. Sandburg’s collections Smoke and Steel (1920), Good Morning, America (1928), and The People, Yes (1936) expanded his scope to include themes of industrialization, economic struggle, and democratic hope. His plainspoken language and musical cadence reflected his lifelong admiration for American folk traditions.

In addition to poetry, Sandburg achieved acclaim as a biographer. His monumental Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926) and Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939) earned him two Pulitzer Prizes and established him as one of the foremost interpreters of Lincoln’s life and legacy.

Style, Themes, and Influence

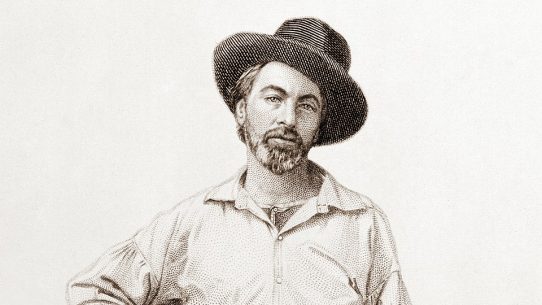

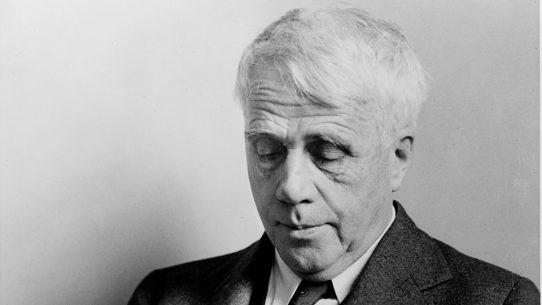

Sandburg’s style is distinguished by free verse, colloquial diction, and a musical sense of rhythm drawn from both speech and song. His poems often read like ballads or chants, echoing the democratic spirit of Walt Whitman while speaking in a voice uniquely his own. He celebrated the resilience and dignity of ordinary people—workers, farmers, soldiers, and dreamers—whom he saw as the true foundation of America.

His themes encompass labor, love, nature, faith, and the promise of democracy. Though often optimistic, Sandburg’s poetry also acknowledges hardship and disillusionment. He sought to reconcile the brutal realities of industrial life with an enduring belief in human progress and compassion. His language, at once simple and profound, opened poetry to audiences far beyond the academy.

Sandburg’s influence extended beyond literature. His fusion of poetry and folk music anticipated later artistic movements, including the rise of the American singer-songwriter tradition embodied by figures such as Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan. His democratic ethos also resonated with generations of poets committed to social engagement.

Later Life and Legacy

In his later years, Sandburg became a cultural icon—a poet of the people who transcended literary boundaries. He continued to write and lecture widely, earning national recognition for his contributions to American letters. His final poetry collection, Honey and Salt (1963), reflects the wisdom and tenderness of his later life, blending meditations on love, age, and mortality.

Sandburg received numerous honors, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964. He spent his final years at his home in Flat Rock, North Carolina, where he remained active in both poetry and music. He died in 1967, leaving behind a legacy rooted in empathy, authenticity, and the belief that poetry belongs to everyone.

Notable Works

Among Sandburg’s most celebrated works is Chicago Poems (1916), a landmark collection that gave voice to the industrial city and the working class. Cornhuskers (1918) continued this exploration of American life, earning him his first Pulitzer Prize. Smoke and Steel (1920) and The People, Yes (1936) reveal his ongoing dialogue with democracy, hope, and endurance during times of social upheaval.

His biographical masterpiece, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939), earned him another Pulitzer Prize and remains one of the definitive accounts of Lincoln’s leadership and humanity. Later collections such as Good Morning, America (1928) and Honey and Salt (1963) display a more reflective, personal tone, showing a poet who matured from chronicler of the people to philosopher of life itself.

Together, Sandburg’s poetry and prose form a mosaic of American experience — honest, compassionate, and enduring in their faith in the common spirit.