Introduction

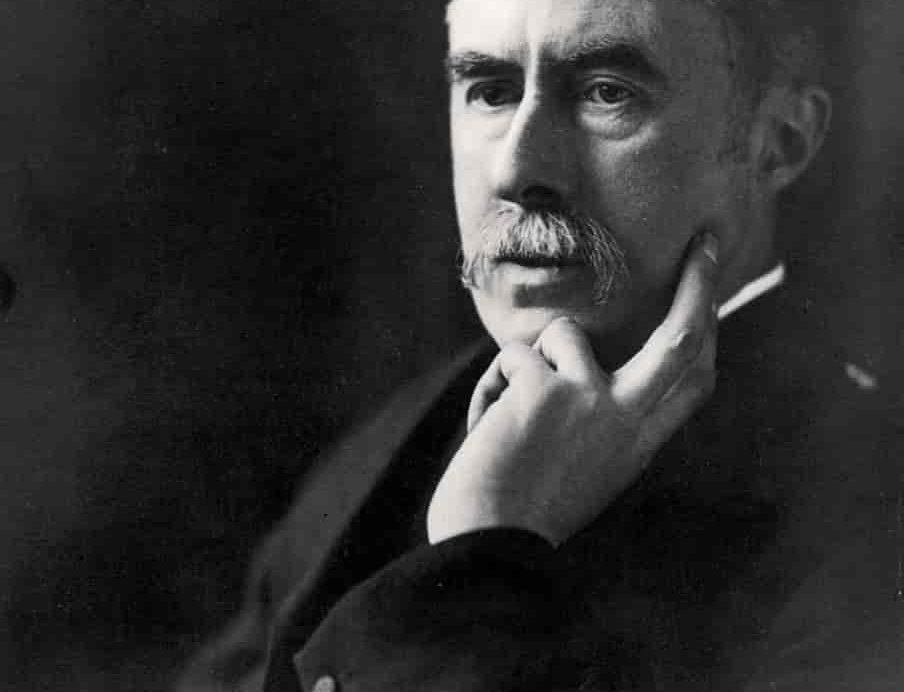

Alfred Edward Housman (1859–1936) was one of the most widely read and quietly influential poets of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Best known for his collection A Shropshire Lad (1896), Housman’s work is marked by emotional restraint, classical precision, and a profound sense of loss and transience. His deceptively simple lyrics — spare in language yet piercing in feeling — captured the melancholy of youth, the inevitability of mortality, and the quiet endurance of English rural life. Although his poetry often evokes nostalgia and longing, beneath its calm surface lies an unflinching awareness of time, regret, and unfulfilled love.

Housman’s fusion of classical discipline with emotional honesty helped shape the tone of twentieth-century English lyricism.

Early Life and Education

A. E. Housman was born on March 26, 1859, in Fockbury, Worcestershire, the eldest of seven children. His father, Edward Housman, was a solicitor; his mother, Sarah Jane Williams, possessed literary taste and religious conviction, which deeply influenced her son. Her death when Housman was twelve left a wound that never fully healed. Reserved and introspective, he excelled academically and won a scholarship to St John’s College, Oxford, where he studied classics.

At Oxford, Housman’s intellectual brilliance was matched by emotional turmoil. He fell deeply — and unreciprocatedly — in love with a fellow student, Moses Jackson, an attachment that would haunt him throughout his life and infuse his poetry with themes of unspoken affection and loss. Distracted and despondent, Housman failed his final examinations, a humiliation that led to years of quiet perseverance before his academic reputation was restored. In 1882, he joined the Patent Office in London while continuing classical studies privately. His independent scholarship eventually earned him recognition as one of the finest Latinists of his age.

Literary Career and Major Works

Housman’s dual life as scholar and poet reflected his divided temperament — intellect in one hand, emotion in the other. His professional career flourished: he became Professor of Latin at University College London in 1892, and later, in 1911, Kennedy Professor of Latin at Cambridge. Yet his poetry remained intensely personal and largely private. A Shropshire Lad, published in 1896, emerged during a period of personal introspection and national unease following Britain’s defeat in the Boer War. Written in simple meters reminiscent of English folk songs and ballads, the collection evokes an idealized rural landscape shadowed by death, youth cut short, and longing for home and peace.

The book’s 63 poems, though modest in tone, struck a chord with readers. Its themes of fleeting youth, stoicism, and quiet heroism resonated deeply, particularly during World War I, when soldiers and civilians alike found solace in its plainspoken melancholy. Housman’s verse carried emotional clarity without sentimentality — a rare gift. The collection’s understated lines, such as “Loveliest of trees, the cherry now / Is hung with bloom along the bough,” and “To an Athlete Dying Young,” became some of the most quoted in modern English poetry.

In 1922, Housman published a second collection, Last Poems, written after Jackson’s death. The volume continued his exploration of mortality and memory but revealed a deeper tenderness and resignation. A posthumous collection, More Poems (1936), expanded his legacy. In both content and style, his work adhered to the classical ideals of precision, clarity, and emotional restraint, masking the depth of his private anguish beneath an austere surface.

Style, Themes, and Influence

Housman’s poetic voice is unmistakable: concise, lyrical, and quietly devastating. His verse draws upon classical structure, English folksong rhythm, and the moral economy of stoicism. Beneath its simplicity lies profound emotional tension — the repression of longing, the awareness of death, and the yearning for a beauty already passing away. His diction is plain but charged with musical precision, allowing deep feeling to emerge through understatement rather than flourish.

Central to Housman’s poetry is the theme of loss — personal, temporal, and existential. Love, in his work, is often unattainable or brief; youth fades quickly, and the grave awaits with inevitability. Yet this fatalism is counterbalanced by courage and grace. The quiet endurance of his speakers embodies a distinctly English form of heroism: stoic, private, and dignified. His classical training shaped his craftsmanship, infusing each poem with clarity of form and emotional balance.

Though Housman’s style seemed out of step with modernist experimentation, his influence proved lasting. Poets such as W. H. Auden and Philip Larkin admired his precision and emotional honesty. His focus on unspoken feeling and moral restraint anticipated twentieth-century introspection. Indeed, in an age of fragmentation and irony, Housman’s sincerity felt radical.

Later Life and Legacy

In his later years, Housman lived an austere, solitary life in Cambridge, devoted to scholarship and routine. His lectures on classical texts, especially those of Propertius and Manilius, were admired for their intellectual rigor and biting wit. Although he remained private about his personal life, his letters reveal flashes of warmth and humor. He continued to honor the memory of Moses Jackson throughout his life, even dedicating Last Poems to him posthumously.

Housman died peacefully on April 30, 1936, at the age of seventy-seven. His ashes were interred near his birthplace in Ludlow, the Shropshire landscape that had inspired his most famous poems. By then, A Shropshire Lad had achieved near-mythic status, beloved by readers who found in its quiet sadness a reflection of their own. Today, Housman stands as a poet of disciplined emotion — one who distilled heartbreak into music and stoicism into art. His lyrics, understated yet enduring, continue to speak across generations to those who find solace in beauty tinged with sorrow.

Notable Works

A Shropshire Lad (1896)

Last Poems (1922)

More Poems (1936, posthumous)

The Name and Nature of Poetry (lecture, 1933)