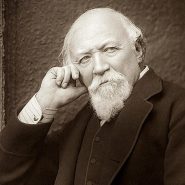

By Robert Frost (1923)

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

Analysis

“Nothing Gold Can Stay” is one of Robert Frost’s most concise yet profound poems. Composed of just eight lines, it distills an entire philosophy of change and impermanence into a single, flawless image. Written in Frost’s signature plainspoken style, the poem explores how beauty, innocence, and perfection are fleeting — in nature, in life, and in the human spirit.

Summary of the Poem

The poem begins with a paradox: “Nature’s first green is gold.” Frost equates the early growth of spring — a tender green — with gold, a symbol of purity and value. Yet this golden hue, the poem insists, is “her hardest hue to hold.” The freshness of new life, like all beauty, is temporary.

As the poem unfolds, each image expands this idea: the first leaf appears like a flower, but its bloom fades; dawn’s golden light yields to the brightness of day. Even paradise — “Eden” — could not preserve its perfection. The final line, “Nothing gold can stay,” delivers the universal truth: all that is precious and perfect must pass.

Themes and Interpretation

Impermanence and Change

At its heart, the poem meditates on transience — the inevitability of decay within all forms of beauty. Frost’s seasonal imagery reminds us that life moves in cycles: every beginning already contains its end. The “gold” of early spring mirrors youth, innocence, and the moments of ideal joy that cannot last.

Innocence and the Fall from Perfection

The reference to Eden evokes humanity’s fall from grace. Frost equates the loss of spring’s early gold with the loss of paradise — the passage from innocence to experience. The poem suggests that beauty’s value lies precisely in its fragility.

Nature as Moral Mirror

As in much of Frost’s poetry, nature reflects human truth. The transformations of leaf, flower, and light mirror emotional and spiritual change. In this sense, the poem reads as both personal reflection and universal lament — a recognition that time spares nothing, not even the most beautiful beginnings.

Structure and Style

“Nothing Gold Can Stay” is written in a single rhymed stanza of eight lines, each in iambic trimeter (three beats per line). The compact form mirrors the brevity of the moment it describes. The rhyme scheme (aabbccdd) creates a sense of closure, reinforcing the poem’s cyclical structure — emergence, fading, and loss.

Frost’s diction is simple, yet every word carries weight. The repetition of short vowel sounds (“gold,” “hold,” “leaf,” “grief”) produces a musical inevitability, echoing the theme of decline. The poem’s economy is deceptive: in its brevity lies immense philosophical depth.

Tone and Meaning

The tone is calm, reflective, and resigned rather than mournful. Frost does not rage against change; he accepts it as part of nature’s rhythm. The poem’s final line is neither bitter nor despairing — it’s an acknowledgment of life’s fleeting grace. This serenity gives the poem its timeless quality: wisdom distilled through simplicity.

Legacy and Significance

“Nothing Gold Can Stay” stands as one of Frost’s most quoted works, admired for its perfect balance of form and insight. It has resonated across generations — appearing in literature, film, and culture, most famously referenced in The Outsiders by S. E. Hinton.

Its enduring appeal lies in its paradoxical beauty: by confronting the transience of life, Frost preserves its meaning. The poem’s brevity mirrors the very truth it expresses — that even the briefest moments of gold are worth cherishing.