Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember writhed its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore—

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating

“’Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door—

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door;—

This it is and nothing more.”

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

“Sir,” said I, “or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you”—here I opened wide the door;—

Darkness there and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, “Lenore?”

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, “Lenore!”—

Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before.

“Surely,” said I, “surely that is something at my window lattice;

Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore—

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;—

’Tis the wind and nothing more!”

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter,

In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore;

Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he;

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door—

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door—

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

“Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “art sure no craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore—

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning—little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door—

Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as “Nevermore.”

But the Raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing farther then he uttered— not a feather then he fluttered—

Till I scarcely more than muttered “Other friends have flown before—

On the morrow he will leave me, as my Hopes have flown before.”

Then the bird said “Nevermore.”

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken,

“Doubtless,” said I, “what it utters is its only stock and store

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore—

Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore

Of ‘Never—nevermore.’ ”

But the Raven still beguiling all my sad soul into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and bust and door;

Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore—

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore

Meant in croaking “Nevermore.”

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom’s core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion’s velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o’er,

But whose velvet-violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o’er,

She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor.

“Wretch,” I cried, “thy God hath lent thee—by these angels he hath sent thee

Respite—respite and nepenthe from thy memories of Lenore;

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe and forget this lost Lenore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!—

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted—

On this home by Horror haunted—tell me truly, I implore—

Is there—is there balm in Gilead?—tell me—tell me, I implore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil—prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us—by that God we both adore—

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden, whom the angels name Lenore.”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!” I shrieked, upstarting—

“Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken!—quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore!

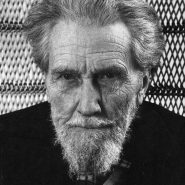

Originally published in The Raven and Other Poems (1845) by Edgar Allan Poe. Public domain.

Analysis

“The Raven” is a dramatic monologue that stages a mind wrestling with grief and the human hunger for certainty. A bereaved scholar seeks intellectual control over an irrational sorrow, but language itself — condensed into the raven’s one-word refrain, “Nevermore” — defeats him.

The poem endures because it fuses meticulous sound craft with a lucid psychology of loss. Read aloud, it feels inevitable; read closely, it reveals how that feeling is engineered.

Form and Music

Each stanza is six lines long, arranged in an intricate pattern of internal rhyme, end rhyme, and refrain. Poe works mainly in trochaic meter, which places stress first and creates a forward-falling cadence well suited to narrative momentum.

Lines bristle with alliteration and assonance — “weak and weary,” “silken, sad, uncertain” — that bind phrases and slow the pace. The echoing -ore sound primes the ear for the climactic “Nevermore,” so that the refrain lands like a ritual response. Meter, rhyme, and refrain collaborate to produce a liturgical atmosphere: the poem feels both sung and sworn.

Setting and Thresholds

The action occurs at midnight in bleak December, with a lamplight chamber framed by two thresholds: the door and the window. Opening the door yields only “Darkness there and nothing more,” a beautifully literal image of grief’s answer.

Opening the window admits the raven, who perches upon a bust of Pallas Athena — a pointed staging that places relentless emotion above reason. Each crossed threshold escalates the encounter from ordinary disturbance to symbolic visitation.

The Raven as Symbol

The bird functions on three levels at once. Literally, it may be a trained creature repeating a single word learned from a “unhappy master.” Supernaturally, it can be read as a messenger or “prophet,” a dark envoy whose replies pronounce doom.

Psychologically, it is the externalized voice of the speaker’s obsession — an intrusive thought that returns with compulsive regularity. The genius of the refrain is that it is semantically empty until the speaker loads it with meaning. “Nevermore” answers every question because it is the answer the speaker most fears and already half believes.

Rhetorical Escalation

The speaker begins with rationalization — “’Tis some visitor” — and with courteous inquiry. When the bird answers, he supplies mitigating stories to contain it: a trained word, a coincidence, a joke. As hope shrinks, his questions lurch toward absolutes — balm in Gilead, reunion in Aidenn. The refrain does not change, but his interpretation does, which is the point. The self supplies despair that the universe refuses to clarify. By the time he demands the bird’s departure, he is really demanding relief from his own thought process.

Theme: The Limits of Knowledge

A scholar in a library expects knowledge to console. Poe shows how knowledge can sharpen pain when the question is metaphysical and personal. The speaker craves a categorical promise that grief will end.

Poetry, not philosophy, offers the truer account: certain wounds are lived, not solved. The final image — the soul pinned beneath the raven’s shadow — is less a curse than a diagnosis of rumination, that looping pattern by which grieving minds trap themselves.

Imagery and Diction

The poem is crowded with tactile and auditory cues: the rustle of curtains, the hollow tapping, the ember that “writhed its ghost.” Elevated diction (“Plutonian,” “Seraphim,” “Aidenn”) enlarges a small room into a cosmology, while homely details — a cushion’s “velvet-violet lining” — keep the scene sensorial and near.

The mixture is quintessential Poe: grand without losing texture, melodious without slipping into mush.

Structure and Control

Critics sometimes accuse Poe of theatrical excess. Yet the poem demonstrates iron control. Repetition is always purposeful: it builds expectation, models obsession, and guides pacing.

The repeated rhyme on “door,” “floor,” and “more” creates a sonic chamber in which thought keeps colliding with the same surfaces. Stanza breaks arrive like little drops in pressure, only for the next wave of sound to rise again. That ebb and surge mirrors a mind that keeps trying, and failing, to quiet itself.

Influence and Legacy

“The Raven” cemented Poe’s international reputation and helped define an American Gothic sensibility that stretches from music to film. Its refrain has become a cultural shorthand for fatalism. Yet the poem’s sophistication can be overshadowed by its popularity. It is not famous only because it is spooky or quotable; it is famous because it demonstrates how prosody can enact psychology — how sound can carry thought.

How to Read It Now

Contemporary readers tend to recognize the speaker’s mental loop: the anxious prediction that returns again and again. Seen this way, the raven’s word is not prophecy but echo.

The bust of Pallas suggests that intelligence alone cannot dissolve grief. The poem does not belittle reason; it simply shows its boundary. Poetry’s unique gift is to make that boundary audible.

Conclusion

The poem endures because it is both meticulously made and emotionally legible. A single word, repeated with ritual precision, becomes a test that every hope must fail. The effect is tragic, but it is earned.

We leave the chamber understanding something about mourning that prose might explain but cannot make us feel: that grief often speaks in refrains, and that the heart sometimes answers its own questions with a word it already knows.